WITH YOUR SUPPORT, WE CAN DO MORE

The Harari people, an indigenous minority in Harar, are being systematically dispossessed of their lands, culture, and history by the growing Oromo majority.

The first time I visited Harar in 2013, my father took me, my sister, and some of my aunts to our family farm, regaling us with childhood stories along the way. But when I returned to the historic city in eastern Ethiopia in 2023, I didn’t dare set foot on my family farm.

As my great-aunt informed me, since the Qeerroo (‘bachelor’ in Afaan Oromoo) in Harar began stirring up trouble in 2018, her Oromo farmhand stopped bringing what she was owed. In her eighties now, she was in no shape to challenge him.

During this tumultuous period, intercommunal violence between Hararis and Oromos spilled over, resulting in many of the remaining Harari farms being forcibly seized by Oromos. In the case of my family farm, two Oromos laid claim to it and, during their quarrel, eventually approached my great-aunt asking her to adjudicate rights to the farm between them.

Paradoxically, they acknowledged my great-aunt’s ownership by conferring on her the authority to bequeath it to them while at the same time denying her the farm. When confronted with this absurd request, she snapped back, “Are you descendants of Ahmed Sherif?”—my great-grandfather.

These kinds of stories have become ubiquitous in the Harari region.

Despite Hararis’ rich farming heritage, over the years many have been dispossessed of their farmlands under varying circumstances. In many gatherings, older Hararis would invariably tell farm stories. Lately, the only stories told about Harari farms concern how an Oromo stole it.

History of Dispossession

In the past, nearly every Harari owned farmland.

Sileshi Wolde-Tsadik described how over 95.5 percent of the land surrounding Harar up to ten kilometers belonged to Hararis, with more than 2,640 individual owners. Sileshi marveled at the meticulous record keeping of Hararis, with some tracing back as far as three centuries, if not further.

Remarking on this tradition, my mother proudly said: “Our grandparents would brush off the dirt from their feet as they crossed the boundaries of each farm so as not to cause cross-contamination or infringe on another’s rights.”

Oromo historians such as Ezekiel Gebissa and Mohammed Hassen, as well as Western ones like Richard Caulk and Sidney Waldron, inform us that Oromos, particularly around the Harari region, were originally pastoralists and learned to farm and borrowed many agricultural terms from Hararis.

While the major driving force behind the Harari exodus in the twentieth century was Amhara hegemony, drastically altering Harari life, today it is Oromo extremism that poses an existential threat. With numerous disturbing stories echoing my great aunt’s, local activists recorded twelve individuals brave enough to speak publicly on this matter.

One story stands out. An elderly woman, while leaning on her walking stick, recounts: “He broke my leg … and told me he has AIDS and would bite me to send me to the afterlife … He defeated me, chasing me away [from my farm].”

Legitimacy Challenged

Since 2018, Hararis in Harar have been quietly enduring a series of injustices, intimidation, and terrorization because of their ethnicity. Only two articles in 2019 and 2020 spoke directly to some of these abuses; one of them was written by me for Ethiopia Insight.

In an effort to defend, justify, or explain the reprehensible actions of their compatriots, Oromo elites interviewed for the 2019 article revealed their underlying contempt for the very existence of the Harari region.

Notably, Mohammed Abdella, a former judge in Oromia, asserted: “Just because they wanted to diminish Oromia, the EPRDF organized the tiny Harari as a regional state [in the early 1990s], while nearly four million Sidama were denied a regional state.”

BACK US TODAY AND SUPPORT PEOPLE-POWERED MEDIA

Notwithstanding that the Harari region is 333.94 square kilometers in size compared to Oromia’s 284,537.84 square kilometers—over 850 times larger than Harari—Mohammed fails to explain how denying Hararis their rights benefits the Sidama people.

Jawar Mohammed, for his part, equivocated on the matter of the Harari state, suggesting it “should have been a special province of Oromia,” but also stating that, “Oromos have nothing to lose from Hararis having their own regional state.”

Jawar’s allusion that Harari being a region is an act of charity is a common trope used to critique Hararis, suggesting they have been unfairly ‘gifted’ a region. The undertones of such comments are that the Harari region should never have existed.

In the same article, Jawar criticizes the “weak and too corrupt” government and “local rivals”, blaming them for the “havoc” in Harar.

However, when Jawar appeared on Oromia Media Network (OMN) in June 2018, he told 43,000 viewers that, “the Harari government should stop stealing Oromo farmland and selling it to Harari diaspora.” The Oromos “took down the Tigray government and it would take less than two days to destroy the small Harari government and make them beggars in [Oromia] towns like Awaday,” he continued.

Jawar would later take credit for helping to resolve the dispute between the Harar city administration and the rural residents of the Harari region, conveniently leaving out his role in fueling the havoc.

Time of Upheaval

After Jawar fanned the flames with baseless claims, the Harari region became uncontrollable.

Mobs regularly roamed the streets brandishing weapons, chanting “ciao, ciao Adare” (goodbye Harari), and banging on the doors of Harari compounds yelling “kinyyaa” (this is ours) and “pack your bags.”

Members of this group made lists of Harari owned homes. Scores of properties belonging to Hararis were destroyed, burned down, or forcibly taken over, including the historical Harari Institute, Aw Abdal.

Diaspora Hararis who fled Ethiopia in the 1980s and 1990s with dreams of returning to their ancestral homeland have been barred, on and off, from the 200-home neighborhood they invested in, which is a stone’s throw away from the historic fortified Jugol in Harar.

Municipal services to Harar were forcibly halted. Later, a ransom letter for 10 million birr was sent to the Harari Water and Sewerage Authority.

Ransom letter for 10 million birr to the Harari Water and Sewerage Authority; Ethiopia Insight

Hararis were harassed for wearing cultural attire and ridiculed for speaking their language, being told “afan ajaawa” (your language stinks) and at times assaulted. They were also extorted as they tried to bury their dead.

Camilla Gibb, a well-known novelist, who revisited Harar in 2018 after having spent around a year there in the 1990s while conducting her doctoral research, told me a few years ago: “I know the elderly and middle-aged [in Harar], I know how they feel hounded in their own city. I have elderly friends whose houses have been taken over in Jugol. My heart breaks.”

At the height of the conflict, the local government provided little to no help to Hararis facing hostility and violence, and could not even protect itself. After a string of mob violence and intimidation of Harari citizens and government officials, the Harari Regional President, Murad Abdulhadi, resigned on June 15, 2018, and shortly after fled Ethiopia.

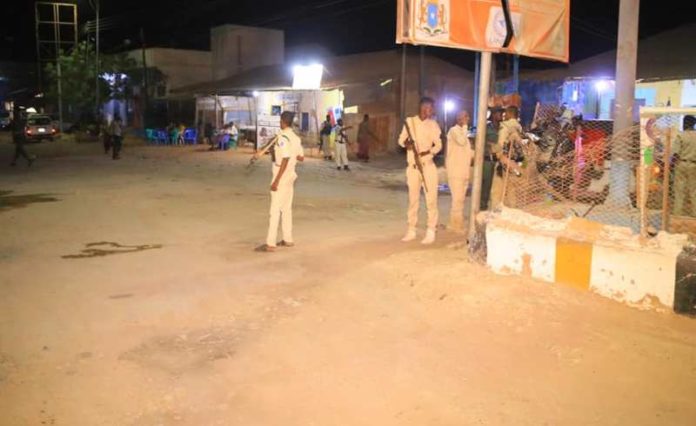

There were reports that the Oromia Special Forces (Liyu Hayil) had severely assaulted the Harari Police Commander, Abdunasir Mohammed, inside the Harari police headquarters. In fact, they would join the mobs, armed and dressed in their fatigues, driving military jeeps draped with the Oromia flag through the streets of Harar.

Oromia Liyu Hail forces accompanying protests in Harar; Ethiopia Insight

In a clear breakdown of local and regional government, no support was provided by federal authorities as crimes occurred daily against Hararis. Given their small population, constant intimidation, and abandonment by their government, Hararis in Harar endured in silence.

Around this time, Prime Minister Abiy addressed an Ethiopian diaspora crowd in Germany where an Amhara person asked him why “nobody is paying attention to the current situation considering the history of Harar and its people that spans over a thousand years?” Abiy’s response to the Harari question was: “All Ethiopians have a rich history.”

Incidentally, neither did other Ethiopians, each with their own rich histories, escape turmoil under Ethiopia’s Nobel Peace Prize winning prime minister.

Shifting Dynamics

In 2019, Prime Minister Abiy upended Ethiopian politics by dismantling the longstanding Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) coalition, which dominated Ethiopia for nearly three decades. In its place he introduced his newly minted Prosperity Party.

In Harari region, the ruling party was the Harari National League. They, along with all the regional ruling parties in Ethiopia except the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), agreed to dissolve and merge into the single Prosperity Party.

In a bid to convince diaspora Hararis that the merger was a good decision, some Harari officials claimed that after the merger they had received significant support from federal authorities, allowing the region to enjoy stability. These officials also pointed to the insecurity in Tigray, suggesting the TPLF’s choice not to merge had directly contributed to Tigray’s problems.

Despite their rosy description of what could be described as a mafia-style shakedown, local officials seem to have mostly curbed overt violence—but at what cost?

As I traveled into Harari from Oromia in March 2023, my driver pointed to the border where streams of illegally constructed houses bled into Harari. Despite their unlawful status, my driver explained these homes were receiving utility services from Oromia.

An influx of Oromos from rural areas have inundated the already densely populated Harari region, placing significant pressure on the integrity of the region and its heritage sites. In 2022, the Head of the Harari Region Construction Bureau sounded the alarm, reporting that over 1,100 hectares of land had been illegally seized and more than 10,000 houses had been unlawfully constructed.

The UNESCO World Heritage Site, one of five historic gates, Assumi Bari; Abdullah Sherif

Government buildings for Oromia, constructed on prime real estate within Harari region, highlight the extent of encroachment. Moreover, all employment positions in these buildings are exclusively for Oromos, serving only the Oromia region.

Harari government initiatives often face interference from Oromo representatives, like in the building of five prototypical Harari houses intended to spur tourism. In response, Oromos insisted on constructing five large modern huts adjacent to them, dominating the Harari ones.

Similarly, a Harari diaspora initiative to support Harari newlyweds in Harar has been undermined, with many participants now being Oromo and some already with families.

While claims persist about Harari’s “bureaucracy favor[ing] ethnic Hararis over others,” in reality the majority of the bureaucracy consists of Oromos who don’t show favoritism towards Hararis. And there are constant reshuffles with key positions slowly being replaced with Oromos.

In Harar, various disputes involving Oromo individuals such as a car accident, dispute over property, or a conflict with a neighbor, may first engage with official bodies, but they will also certainly have to deal with an Abba Gada (Oromo leadership).

As Oromo elites valorize traditional Oromo systems of conflict resolution, in Harar they serve to destabilize official authorities, rendering traditional Harari institutions and official ones irrelevant. Under the guise of tradition, mob rule prevails with Oromo chieftains dispensing Oromo justice.

Further assaults on Harari’s indigenous minority were on full display when the National Electoral Board of Ethiopia in 2021 denied Hararis living outside of the region the right to vote in Harari region. Harari politicians challenged this action at the federal court and won.

Federal Protections

The only thing that has protected Hararis, at least nominally, is the right to self-determination enshrined in Ethiopia’s multinational federal constitution.

As long as the Ethiopian constitution requires the existence of the Harari region with its own government and a minimum number of Harari representatives, overtly removing Hararis is difficult. This forces those who seek to dispossess Hararis and dissolve their state to operate surreptitiously.

With their minuscule population, Hararis stand little to no chance of winning a seat in a general election within the Ethiopian political landscape. This puts them at risk of total disenfranchisement.

In Harari region, according to the 2007 census, Hararis make up about nine percent of the population, and while there are significantly more Hararis outside of the Harari region—due to the history of forced displacement—they account for less than one percent of Ethiopia’s population. Conversely, Oromos make up the majority population in Harari region (56.4 percent).

However, a small population is not an excuse to deny indigenous people their rights to self-governance and to maintain their identity, language, culture, and history in their native land. Yet, the size of the Harari population is always cited as reason to deny Hararis their rights without ever asking why they are a minority in their homeland.

Such rhetoric dominates the discourse surrounding the existence of the Harari region. For instance, Sandra Joireman and Thomas Szayana write: “The [Harari] are overrepresented in parliament and the Council of Ministers, as they are given one representative in each body for a group that is 0.0005 percent of the Ethiopian population.”

Since people cannot be divided into fractions, if one representative is considered overrepresentation, it could be construed that Hararis do not deserve any representation at all. What they should have argued is that those underrepresented, or not at all, should be.

BACK INDEPENDENT MEDIA TODAY. AMPLIFY OUR WORK!

Instead, we continue to see this contorted logic used to pit disenfranchised people against each other, and to uphold arguments that one group not having their rights recognized can somehow be used to justify denying the rights of others.

The other objection lobbed at the existence of the Harari state is that it’s undemocratic because of the provisions that safeguard the representation of indigenous Hararis. However, many democracies have made provisions for minority and indigenous people, ranging from affirmative action measures to self-governing provisions and reserving seats for them in legislatures.

Just as with its other attributes, Harari region’s constitution is unique compared to other Ethiopian regions. While these provisions ensure the indigenous population is always protected, critics decry the empowerment of this indigenous minority.

Through the bicameral system implemented in Harari region, Hararis secure their rights by virtue of the first chamber, while the second chamber offers political representation to all residents, thereby striving to strike some balance in the region.

These principles, in fact, strengthen democracy, by enshrining the rights of minority and indigenous people who have historically been marginalized and discriminated against. Opponents who decry the Harari constitution propose no alternatives other than its dismantlement, which would only lead to the complete disenfranchisement of Hararis.

Disputed Histories

The history of the Harari people is crucial in understanding the current configuration of their region.

Jawar, after contributing to some of the chaos in Harari, periodically swoops in with messages of peace and brotherliness, saying things like: “The Oromo people and the Harari people are the same. We have lived drinking water from one river for a thousand years.”

These calls for peace ring hollow, but more concerning is the revisionism in his messages. Only Hararis have a history spanning more than a thousand years in the region, a fact that underscores their claims of indigeneity on which they stake their political rights.

Jawar knows the Oromo people arrived in the region in the latter half of the sixteenth century, so his invoking of “a thousand years” is calculated, and serves to undermine Harari claims.

The consensus among historians is that the Harari progenitors once occupied large areas of the Harar plateau. Hundreds of ruined urban centers that dot the region attest to an ancient and expansive civilization, all attributed to the ancestors of the Harari people. Their destruction is attributed to Oromos.

As this civilization was collapsing in the sixteenth century, the survivors retreated behind the walls of Harar and became known, in the Harari language, as “Gey’usu” or “the people of the city.” Several historians described the continued survival of the Harari people as an “interesting phenomenon” and “one of the mysteries of history of the region.”

Once relegated to inside their citadel, Hararis continued to govern themselves during 212 years of dynastic rule through their own localized hierarchies, courts, administration, and religious institutions. They also had defined boundaries, maintained an extensive taxation system, minted their own currency, and maintained diplomatic relations with other political communities.

Having enjoyed a millennium of self-administration, including within the Adal Sultanate from 1415 to 1577 and later as an independent autonomous emirate, it’s a false premise to ask why Hararis should be given statehood.

Harari independence ended in 1887 by Menelik II’s invasion. This conquest led to the violent incorporation of Harar into the Ethiopian empire, culminating in the Battle of Chelenqo. Hararis have always resented the Oromos’ minimal participation in this battle, often accusing them of betrayal.

Caulk notes Harari-Oromo tensions at the time which may have led to the limited cooperation. He recounts a conspiracy by Orfo, the prominent Oromo leader, who went so far as suggesting to Menelik II that his soldiers mutilate the Harari men and women after the battle.

Despite a complete defeat, Hararis managed to parley with Menelik II and secure some rights, although these were not honored. For almost a century, Hararis mounted several resistance movements, both peaceful and violent.

It was not until 1991, when they were granted a chance to regain some autonomy and self-determination, that Hararis accepted being Ethiopian.

History Appropriated

Today, this history is being appropriated for political ends by Oromo elites. In the past, Hararis were not afforded many opportunities to tell their stories, which explains why symbolic expressions were deployed and continue to be crucial for Hararis.

After 1991, Hararis began commemorating the Battle of Chelenqo more openly, even organizing trips to the site of the battle and building a monument in the town square of Harar.

Recently, however, Oromia region constructed its own monument at the Chelenqo site. Consequently, this site has been reimagined as part of the ‘Hararge’ Oromo history with no real reference to Hararis. These actions represent a blatant erasure of Harari history.

Harari Chelenqo Monument in the center of Harar city; Abdullah Sherif

While Hararis no longer organize trips to the Chelenqo site, they do gather at the town square on the anniversary of Chelenqo. During the period of instability, this commemoration was interrupted with participants being pelted with stones. Nevertheless, this event is still observed by Hararis every year, albeit in a more subdued manner, while it is contested by Oromos both in situ and virtually.

Oromos have numerous battles and massacres to commemorate, with many potential sites to construct monuments. This new focus on Chelenqo, a battle where the main actors were Hararis, appears far from coincidental.

While Oromos have inhabited Hararge for some time, so too have many other groups. Yet often ‘Hararge’ is used to refer exclusively to Oromos living in that region.

Historically, Hararge—derived from Harari words, Harar and gey (city), meaning the city of Harar—was used to describe the city and later became the name of a large province in Ethiopia.

Its usage has evolved over the years, but what is emerging now is an identity describing mostly a subset of Oromos. The problem with this new Hararge identity is that it’s often used to describe what is quintessentially Harari without any attribution of Hararis.

Unaddressed Grievances

Much attention has been given, and rightfully so, to the unimaginable crises in Tigray, Afar, Oromia, and Amhara. While the largest ethnic groups struggle for survival and jockey for supremacy, so many other Ethiopian stories become lost.

Under the cover of this chaos and confusion, further atrocities occur. The smaller, less noticeable casualties of these conflicts often go unseen and unaddressed. The plight of Somalis is less known, the suffering of the Gedeo people overlooked and forgotten, and some like the Benishangul are unjustly demonized.

In the case of Harar, while widespread massacres may have been averted, the people suffer in silence as the intention to erase Hararis persists. The tactics are subtler, but their intent is to dispossess the Harari people in a process akin to ethnic cleansing.

The history of Harar is being altered, its culture appropriated, the land and property stolen, and the politics undermined. I recently asked a local resident if the violence had stopped. “They got everything they want… there is no more need for violence,” he replied.

Despite widespread knowledge of the abuses occurring in Harar, they have largely been ignored. Neither politicians, the media, nor rights groups have addressed the Harari people’s pleas.

Harar was one of the proverbial canaries in the coal mine as Ethiopia has lurched from crisis to crisis. The collective inaction in Harar signaled a permissibility to commit any kind of crime. As each community took its turn in enduring its share of abuses, those inflicted on Harar have never been properly addressed.

HELP US BRING ETHIOPIA NEWS TO MORE READERS

Query or correction? Email us

Main Image: The Harari Heritage House; Abdullah Sherif

This is the author’s viewpoint. However, Ethiopia Insight will correct clear factual errors.

![]()

Published under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International licence. You may not use the material for commercial purposes.