It was not until Fadumo* was sitting in an unfamiliar room on Mogadishu’s outskirts, and the smile vanished from her mother’s face, that the 16-year-old realised she was not going on holiday to Dubai.

In retrospect, there had been clues before they left England, when her mother suddenly announced, in 2022, that the two of them were going on holiday in a few days’ time. But it had been a difficult school year and Fadumo welcomed the idea of a break as a chance to repair their crumbling relationship.

Onboard the aeroplane, her mother had explained that they were flying via Mogadishu to see their family.

But Fadumo was sure something was wrong, so she searched the hotel room and found the plane tickets. Her mother’s flight was in a few weeks but hers was the following summer.

When her mother told her it was an old ticket, Fadumo asked to see the new one. Her mother said she did not have it but she would have it tomorrow.

Tomorrow never came. That evening, Fadumo was in a car with her family. “Everyone was deadly silent. No one would talk to me,” she says.

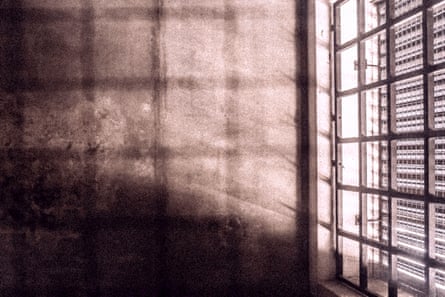

As they left the city lights behind, and the roads became bumpier, she realised they were leaving Mogadishu. “We stopped outside a compound. It was really dark so I couldn’t see the writing on the sign above the door. I thought maybe we were there to visit someone.”

The place was intimidating, surrounded by barbed wire, with tall gates guarded by armed men. A man told her to come inside and join her family. Everything suddenly came into focus.

“I walk in and [my family] look like they’ve seen a ghost. But also like they all know something I don’t,” she says. “I’m looking around, asking questions, making small talk, and I notice they’re locking the gates.” Fadumo’s confusion turned to anxiety, and she asked: “What are we doing here?”

Finally, she was told the truth. “My mum takes me by the hand and says: “This is where you’ll stay. Inshallah, you’ll become a better person.”

Shock and anger hit Fadumo. “I felt so betrayed,” she says. Then one of the men told her mother it was time to go.

Dhaqan celis is a well-known phenomenon in the Somali diaspora, where parents often feel their children have become too westernised. It can be translated as “return to culture” and may just involve being sent to live with relatives in Somalia. But in recent years, dhaqan celis has come to mean cultural re-education centres, offering an experience like a boarding school or boot camp, with a robust Islamic education and strict routines to straighten out attenders.

Dhaqan celis centres emerged as children of refugees who fled Somalia’s civil war in the early 1990s reached adolescence. Facebook and Google feature innocuous pictures of exteriors and promises that the centres rehabilitate young people who disobey their parents or use drugs. Some feature videos of young Somalis talking positively about their experiences at these centres.

But many Reddit threads and TikTok videos feature anxious young people who fear their families plan to send them away for dhaqan celis. Younger Somalis know that being sent “home” could happen to anyone at any time – and there is little anyone can do.

Cousins or family friends can disappear after being caught drinking or “acting out”. If anyone asks where they are, the response is vague: they are in Hargeisa, or Puntland, or with an aunt in Nairobi, or at a boarding school.

These stories inspire fear because it is an open secret among Somalis that these dhaqan celis centres are places with little or no oversight, where anything can happen.

Fadumo was held at al-Xarameyn, Mogadishu, with girls from the UK, continental Europe and North America. Once her family left, it got worse. “They told me to give them my phone but I refused. I put it in my bra, thinking they wouldn’t touch me there. One of the guards held my arms, another pointed a gun at me, and a third one went through my bra and got it from me. They were all laughing.”

A strict daily regime of religious teaching and violence began. “The staff hit me with a wooden stick after I refused to do something,” says Fadumo. “I can’t even remember for what now. It was more than one person hitting me for about 20-30 minutes, just hitting me everywhere. Then they tied me up with chains.”

Any deviation from the rules had brutal repercussions. Waking up late or incorrectly reciting from the Qur’an could lead to beatings.

During her time there, Fadumo’s health deteriorated significantly. “The food they served there was like green glue. I don’t even know what it was. I’d give my food away; I just didn’t eat.”

As she lost weight, her mental health also degenerated. “My body felt dissociated from my mind, like this person wasn’t me,” Fadumo says.

The Guardian has spoken to two other British Somalis who allege that they were also detained at al-Xarameyn for months, and subjected to beatings, solitary confinement and psychological abuse.

One young British woman, Bilan*, says she was sent away in 2021 and detained for two years: first at al-Xarameyn, and then, after she tried to escape, at another centre called Luqman al-Hakim, also in Mogadishu. She alleges she was abused at both centres.

Like Fadumo, she says she lost weight, often fainting because of a lack of food and water. Bilan, now 22, claims brutal beatings were routine at both places. Luqman al-Hakim is a particularly notorious centre, with several online accounts of abuse there. “They beat me into submission,” one woman said on YouTube. She also claimed that sexual abuse was common, including of detainees under 16.

Al-Xarameyn and Luqman al-Hakim did not respond to a request for comment regarding the claims made by the former detainees interviewed here.

Two young American Somalis, speaking on condition of anonymity, had similar stories. One believes his family wanted him dead when they discovered he was gay. They tricked him into going on holiday to Nairobi and told him, once he arrived, he was going for dhaqan celis. He escaped that night, finding his way to the embassy and back to the US. Another former detainee described shackling, beatings and solitary confinement.

Bilan said her feet became so swollen from lashings at Luqman al-Hakim that she could not put shoes on. Sometimes, she vomited from the shock. “They tied my legs up, blindfolded me and put me in ‘room 6’, where they lock you up, and beat me up with drainpipes.” She also claims she was sexually assaulted in the first centre by one of the men running the facility.

Hodan*, from Manchester, was 22 when she was detained in al-Xarameyn. She had been growing apart from her family and calls herself the “black sheep” of her siblings. As Hodan was an adult, she did not believe dhaqan celis could happen to her. However, the centres have no age limit.

Like Fadumo, she had no idea what lay ahead until it was too late. When they arrived, Hodan’s father asked: “Do you know where we are? This is where you will die.” Understanding him to mean that he would leave her there for the rest of her life, Hodan says she had a terrible panic attack. “I thought I must be walking into my grave,” she says.

At one point, Hodan spent five days locked up alone, with one toilet break and one meal a day. “It’s about making you feel like you can’t do little things by yourself because what they want you to do is to leave the place and be reliant on whoever is meant to control you,” she says.

As they operate outside the law, it is unclear how many centres exist. Estimates are difficult in Somalia, where the US and British embassies have a limited presence because of the “constant threat of terrorist attack”.

after newsletter promotion

The US embassy in Nairobi said it had helped about 300 citizens in Somalia and Kenya, where dhaqan celis is also prevalent, after they were held in “unlicensed facilities” against their will.

Bilan says these centres are all over Mogadishu. When she was finally allowed out of the centre where she was held, she saw another one across the street.

Guleid Jama, a Somali human rights lawyer who has represented former captives, believes hundreds of US and European citizens are trapped in these “detention centres”. With so little awareness of them, or political will to confront the problem, many people are left in limbo, Jama says. “There is a huge need for a legal framework, as currently there isn’t really one.”

The lack of regulation can be fatal: in 2014 an American teenager died in a “boarding school” in Somalia’s north-east state of Puntland. Ammar Abdirahman’s family said they wanted to get him away from gangs in Minneapolis and let him learn about his culture.

Instead, they say the 17-year-old was tortured and killed, pointing to photographs showing his badly beaten body. An autopsy suggested he was strangled. Somali authorities said they looked into his death in 2015, but it is unclear whether an investigation was even carried out.

According to US researchers last year, parents turn to dhaqan celis largely for fear of losing control of their children’s behaviour and values.

The 1991 civil war upended the lives of nearly 2 million Somalis and in much of the country fighting continues. Somalia is still one of the world’s most dangerous countries. “Because they were refugees, they couldn’t necessarily visit home often. So they couldn’t revise the idea of ‘home’,” says a co-author of the study, Farah Bakaari. “Somalia looks very different right now.”

This, combined with social alienation in their host countries and fear of cultural “corruption”, created a “perfect storm” of conditions that make Somali parents feel they should send their children away, says Bakaari.

Sorrel Dixon, a UK lawyer who specialises in child abduction, has spoken to parents who send their children abroad to places like dhaqan celis centres. “Many parents are probably reasonably well-intentioned, and think that if they send their children to be within the bosom of their family or country of origin, that somehow that is going to make them see the light and straighten them out,” she says.

The problem is so pervasive that Kenya’s Directorate of Criminal Investigations (DCI) said last November that it was working with other government agencies and the US embassy “in the fight against illegal rehabilitation centres in the country”. The DCI said foreign nationals, primarily from the US and Europe, were being subjected to “inhumane conditions” and “physical abuse”.

The DCI said: “It is after their arrival at the centres, and their travel documents get confiscated, that the youths learn that they are not on safari to learn their beautiful culture but a behaviour-rectification centre where the cane is administered thoroughly.” The DCI raided one Kenyan rehabilitation centre in April, rescuing 10 foreigners, many of whom were Somalis raised in the west.

The legal implications for people who take a child abroad for dhaqan celis are unclear. Very few detainees go to the authorities on their return home. Many have little trust in the authorities and point to the lack of action when they were being held against their will; or they believe nothing will be done if they do report it. They might also fear further reprisals from their family or feel the emotional toll of reporting a parent is too high.

For Hodan, it was a combination of these factors. Her friends grew worried when she stopped responding to messages and did not return from what was supposed to be a holiday. One friend called the police in the UK and the British embassy in Mogadishu but nothing was done, so the friend threatened the family with legal action and reporting them to the social services if they did not bring Hodan back.

Meanwhile, realising her only escape was to “play the game”, as she puts it, Hodan became quiet, respectful and promised her father that she had changed. After 91 days there, alongside her friend’s legal threat, Hodan was allowed to leave.

“I came back with a different perspective on life. I’m a lot more guarded because I never want to be put in that position ever again,” says Hodan. She no longer sees her family.

Fadumo, who was still only a minor when she returned, had no choice but to return to her mother in Birmingham. Before she was taken to Somalia, she was known to social services.

Sometimes, Fadumo says, her mother locked her out of her home as punishment for breaking rules. Once she was left outside all night before an exam and went to school hungry and unwashed.

Fadumo begged social services to take her complaints seriously, saying she was experiencing abuse. But she says they ignored her and told her to obey her mother. Fadumo believes no one at her school or in social services listened to her or tried to understand her situation before she disappeared. As a result, she felt that contacting local authorities or the police was futile. And, she added, no matter how betrayed she felt, she did not want to get her mother into trouble.

It is hard to comprehend how young Britons, barely out of childhood, can disappear abroad without anyone noticing, only to reappear months or years later, traumatised by abuse – and for there to be no consequences.

The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office said it was aware of conditions reported by young British citizens who had experienced cultural rehabilitation centres in Somalia but consular support there was severely limited. An FCDO spokesperson said: “Any cases of physical or emotional abuse experienced by young British people are totally unacceptable and we stand ready to help those who need our support. Anyone concerned about a British national in Somalia or Kenya should contact us.”

On her first night in the centre, Fadumo started a tally on the wall. She knew when GCSE results came out and when the new school year had started. Her life in London was moving on without her.

Fadumo thought her way out of her restrictive life was to excel in her education, go to university and find a career she cared about; she would become financially independent and free. Those dreams have been destroyed.

After months in captivity she became seriously ill with malaria, which she says many other detainees also contracted. She received medication from a man she calls a “makeshift doctor”.

Her declining health, and the intervention of a relative who disagreed with her detention, pushed her mother and staff at al-Xarameyn centre to agree she should be released, nine months earlier than planned. But by the time she returned to Britain the school year had started and Fadumo was refused entry to the sixth form, despite achieving the required grades.

Fadumo believes her health has not fully recovered. Months later, an infection left her in hospital because of a weakened immune system. “I used to have a bit of meat on me; I used to have chubby cheeks,” Fadumo says. “I don’t have those any more.”

She is trying to move on and wants to go to university and leave her family. But she says her biggest realisation from her experience was that she could only rely on herself.

“I grew up thinking that the police and social services are here to help you. Imagine you’ve been going to school every day for five years and they’re telling you, ‘We’re always here for you’. Then as soon as you’re actually in a situation where you need serious help, they do nothing.

“It felt like no one cared about me. It still does.”

* Names have been changed