Voter registration is up, as confidence in election technology grows, but trust in the electoral commission continues to flounder.

From tomorrow, 25 February, and over the next two weeks, 93 million registered voters are expected to go to the polls. That’s 16.7 million more than the combined voter population of the other 14 West Africa countries. Voters will be electing candidates for 1,491 constituencies, comprising 1 Presidential constituency, 28 Governorship elections, 109 Senatorial Districts, 360 Federal Constituencies and 993 State Assembly seats from 18 registered political parties. The incumbent president and 28 of the 36 state governors reaching term limits guarantees new leadership at many levels of government.

It is a massive logistical exercise. It doesn’t help that since the return of civilian rule in 1999, the election process has been riddled with malpractice, vote-buying and sponsored violence. Not surprisingly, voters have turned away from the ballot, and in significant numbers. Consecutive elections in 2007, 2011, 2015 and 2019 elections delivered declining voter turnouts of 57%, 54%, 44%, and 34.75% respectively. Contrast that with the optimism in the democratic process demonstrated between 1999 and 2003, where turnout increased from 52% to 69%.

With disenchanted citizens increasingly rejecting elections, officials turned to technology via the introduction of the Bimodal Voters Accreditation System (BVAS) and the Independent National Electoral Commission Result Viewing Portal (IReV).

Stakeholders have lauded the introduction of these technologies. For many, it explains the high number of newly registered voters and improved electoral consciousness, especially among the youth. It is expected that these technological innovations will be the magic wand that improves the credibility of the elections.

The BVAS: Prospects and Unique Strengths

The BVAS is a digital device that authenticates and accredits voters via fingerprints and facial recognition. The device also captures images of the polling unit result sheets (Form EC8A) and uploads the image online. Following its introduction, the device was tested in the Isoko South Constituency 1 by-election in Delta State on 10 September 2021 and in Anambra, Ekiti and Osun off-cycle gubernatorial elections. One of its demonstrated strengths was the elimination of manual voter verification, which had previously left several loopholes for election manipulation.

The BVAS is accompanied by the IREV, which allows citizens to view the results uploaded by the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC). The BVAS is supported by a strong legal framework – the Electoral Act. The absence of the Act previously, in the three elections between 2011 and 2019, fundamentally weakened the results verification process.

Challenges with BVAS

There are two main sets of challenges to the elections technology infrastructure – those arising from an absence of adequate support systems, and those arising from poor back-end security and reliability.

To the first are questions surrounding the readiness and capacity of the electoral umpire INEC. INEC’s far from salutary track-record managing election logistics is littered with postponements and delays – in one notorious case, the postponement of an election less than six hours before it was supposed to be conducted.

Related to this is the availability and adequacy of supporting infrastructure, specifically power and internet connectivity. Throughout Nigeria, the road network is poor, internet service providers largely unreliable, and less than half the country’s population has access to electricity, all of which pose a major challenge to the country’s adoption and effective use of election technology.

It is more than a bit worrying that INEC only employed the staff handling the BVAS three weeks to the election. Will their training be sufficient? It is instructive that a tribunal cancelled 774 polling units in the 16 July 2022 gubernatorial elections for multiple voting despite the use of the BVAS suggesting, disturbingly, that the technology is only as good as those who use it.

The judgment directly indicted INEC and its use of ad-hoc staff given that there were no known reports of multiple voting in those polling units. It is unclear if INEC has recruited sufficient and well-trained Registration Area Centre technicians, INEC’s roving technical experts able to resolve any problems with the BVAS.

Experience in Nigeria suggests this may not be the case. This dearth of skilled manpower ultimately deepens distrust in election technology, reviving the perennial issue of the credibility of elections.

The trust gap

Election authorities were attracted to technology because it supposedly eliminated opportunities for election fraud, risks of programme error, virus attacks, software attacks or system hacking, even the prospect of fake polling stations.

Back-end issues with databases and servers are complicated and the source of much dispute. In Nigeria’s 2019 general elections, INEC’s server issues became central in the case brought before the elections tribunal by a presidential elections loser.

However, it is the issue of the electronic manipulation of the results that is most worrying. Allegations that election technology companies colluded in the manipulation of results in favour of one candidate have been made across a range of jurisdictions, from the US (specifically the state of California in the Democratic Party primaries in 2016), to Kenya (most notoriously in 2013 and 2017), Congo-Kinshasa (2018), Venezuela (2017) and the Philippines (2022). The credibility of ‘smart elections’ is under considerable threat.

The growing disenchantment with election technology worldwide is perhaps best captured by the lawsuit submitted by Raila Odinga, the first runner-up in Kenya’s 2022 presidential election, suggesting that wholesale adoption of electoral technologies did not diminish election rigging. Evidence shows that technologically advanced countries are increasingly apprehensive about completely shifting to technology, and some, like Germany, are even cutting down on the use of election technology because of security risks.

While INEC has presented the BVAS as a nearly perfect system, the enthusiasm for the BVAS has been matched by almost equal amounts of scepticism. Without an independent oversight organisation, Nigerians are at the mercy of INEC – problematic, given INEC’s perverse incentives on the issue of trust. Ultimately, it boils down to the question: who oversees those that control the technology?

An Afrobarometer report released on 2 February, 2023, indicated that trust in INEC has declined 12% since 2017. Only 23% of Nigerians say they trust the commission “somewhat” or “a lot”; 78% express “just a little” or “no trust at all” in the elections body. Independent oversight would benefit INEC as well as all Nigerians.

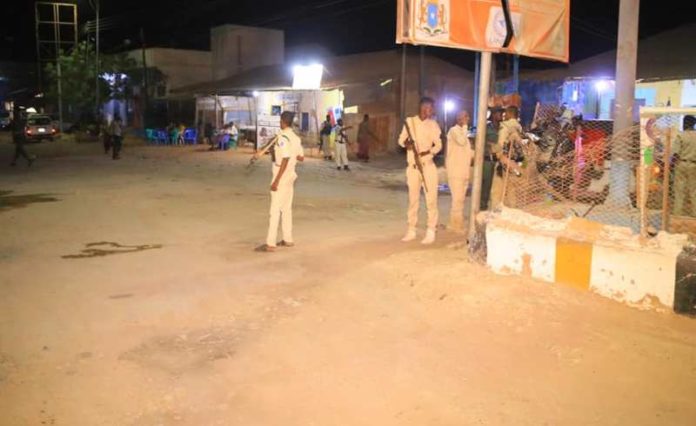

Ultimately, elections are a mirror of society. Even if the BVAS works perfectly, politically-sponsored violence, vote buying, and other attempts to undermine the will of the people remain. You might digitise elections; you can’t digitise integrity.

Dengiyefa Angalapu is a Research Analyst with the Centre for Democracy and Development. He is a Political Scientist interested in research and teaching on development challenges in the global south, specifically focusing on issues around climate change and conflict, policing, crude oil-related violence, maritime security, terrorism, environmental politics and sustainability. He is also interested in issues of democracy and human rights. Dengiyefa Angalapu has vast experience working as a researcher on violence in Nigeria’s oil-rich Niger Delta, northcentral, northwest and northeast regions.